Despite rapid developments in software adoption across Japan businesses and consumers alike, the use of seals (hanko) as the standard mode of authentication will likely continue, due to deeply embedded social practices.

Signatures? Seals? What’s the difference?

When comparing the differences in corporate culture and general business practices between Japan and the rest of the world, more often than not we chance upon the concept and usage of seals (or “hanko”, as it is called in Japanese).

These seals are indeed used for authenticating across important documents during business and investment transactions – but in fact, they occupy a significant role not only in corporate life, but in overall personal social life as well.

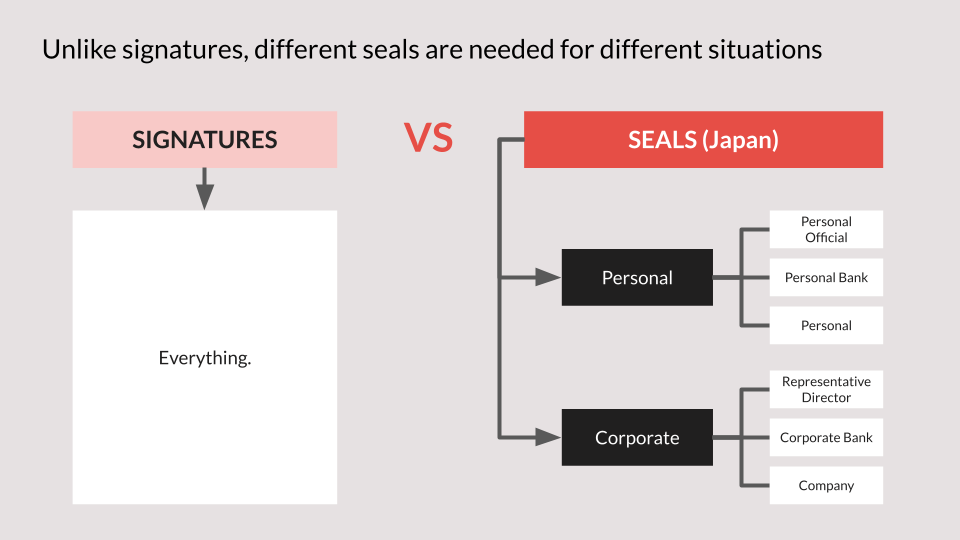

It would be important to therefore begin by stating the main difference between signatures and seals: our concept of signature is applicable across all and any forms of documents and transactions that require authentication, regardless of its purpose or our position in our capacity as signers.

However, on the other hand, there are different seal types that are differentiated between personal and business categories, and furthermore, different seal subtypes within each category depending on the specific purpose of the seal.

How seals work in Japan

What exactly is a seal, in the first place? A seal or hanko is a wooden block with a customized rubber stamp that can be used in personal or business situations. It is standard in Japan for the design on the rubber stamp is customized based on one’s family initials, with varied typographic differences for different uses. Seals can be divided into 2 main categories: personal and business.

For personal use. Every person living in Japan, regardless of nationality, ought to have the 3 main seals ready at their disposal for conducting daily life matters. Firstly, the personal official seal (or jitsu-in) is used for key official documents, such as setting up a company, filing taxes, buying real estate, and so on. As the jitsu-in is an official seal, the rubber stamp design is usually customized with old kanji fonts with the full name of the user, and it also has to be registered with the ward office to certify its authenticity with its user.

Secondly, there is the personal bank seal (ginko-in), which is primarily used for bank-related processes. Since historical times, banks have held great importance amongst socio-economic institutions and therefore have been attributed with their own specific seal as well. The ginko-in rubber stamp is also usually designed with old kanji fonts albeit with only the family name of the user. Registration with the ward office is not required – it is simply registered with the respective bank you open your bank account at upon use.

Thirdly, the personal seal (mitome-in) is most commonly used for daily activities, such as invoices, receipts, or personal signatures off minor transaction documents. This rubber stamp design is usually customized with modern kanji font, with only the family name – which is why templates of common family names can also be commonly found across various retail stores in Japan. There is no need to register this seal.

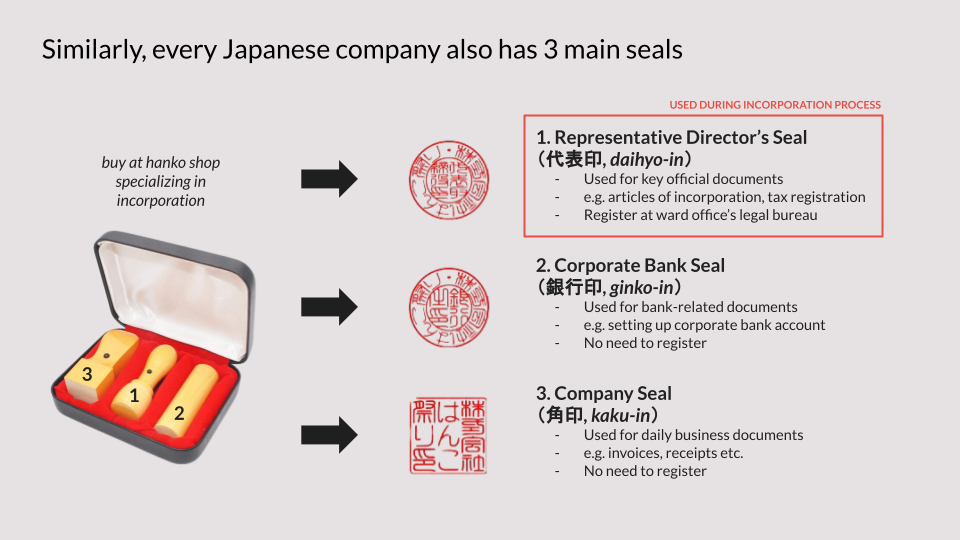

For business use. The subtypes of business seals very similarly reflect their subtype counterparts of personal seals, in terms of their use cases. Due to the level of importance, usually all the stamps (but not necessarily) are designed in old kanji fonts.

Firstly, the representative director’s seal (daihyo-in) most closely mirrors the personal use case of the jitsu-in: it is also used for key official documents, but in this case in the capacity as a company’s representative director to sign off matters. Similarly has to be registered – not at the ward office per se, but at its legal bureau office, usually done once the incorporation registration documents have been submitted. This is usually a circular rubber stamp with the company’s name in the circumference, and the kanji for representative director written in the middle.

Secondly, the corporate bank seal (also called ginko-in) most closely mirrors the personal use case of the ginko-in: it is also used for all bank documents, but in this case for corporate bank accounts associated with the company only. Similarly, it is registered automatically at the respective bank where the corporate bank account is created and used. This is usually a circular rubber stamp with the company’s name in the circumference, and the kanji for bank written in the middle.

Thirdly, the company seal (kaku-in) most closely mirrors the personal use case of the mitome-in: it is also used for daily transactions such as invoices and receipts, but in this case for transactions that occur on the company’s balance sheets. There is similarly no need for this to be registered. This is usually a square rubber stamp with the company’s name.

The future of seals in Japan

As we can see, the practice of using different seals for different purposes is deeply embedded in Japanese history and perpetuates itself across everyday life in both personal and business aspects. So, what is likely to change as Japanese companies gradually migrate to the cloud over the next few years?

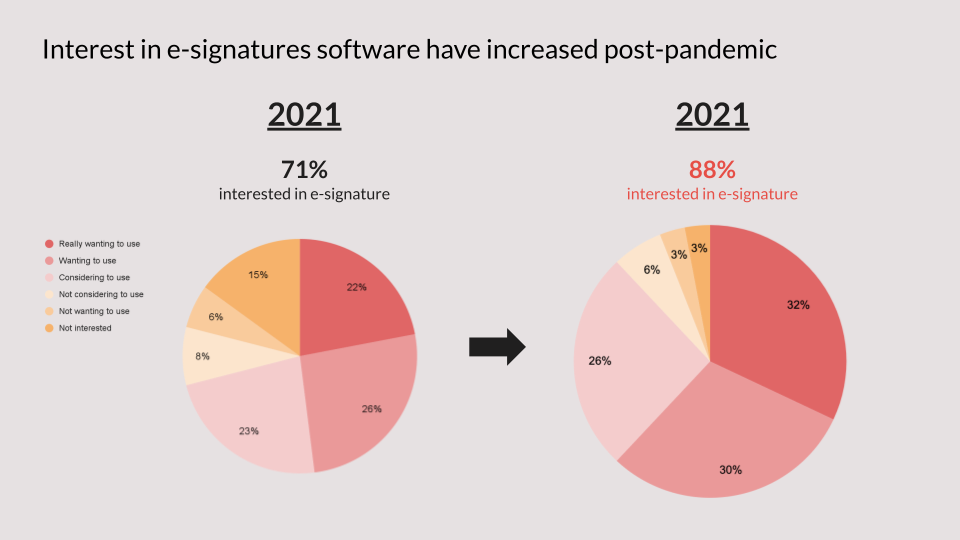

A notable trend that has recently emerged is the rapid adoption of e-signature software in corporate Japan post-pandemic. According to a survey conducted by Docusign in 2022 (*1), the % of companies that are at least interested in using e-signature software in their business operations have increased from 71% in 2021 to over 88% in 2022.

Furthermore, 93% of those who have used the e-signature software answered that it was “convenient,”, with the top reasons being that: a) Seals are no longer needed, b) Can be used anywhere, anytime, c) The location of documents being circulated is known, and d) Electronically recorded records can be checked later.

Nonetheless, a caveat should be acknowledged. Insofar, as e-signature apps are increasing in Japan, the main usages are still providing digital hanko image equivalents of their physical stamps, rather than radically accepting signatures en masse.

As the existence of seals holds a certain historical, social and cultural significance in Japan, it is more likely that the practice of using various seals will continue, this time migrating to the cloud. In this sense, the mass adoption of signatures like we understand in the english-speaking world would still be some time away for Japan, if at all.

*1 DocuSign Japan, “The rate of use for e-signatures has doubled over a year – DocuSign publishes ‘E-Signature Report 2022’”, 2 Aug 2022

By Jorel Chan | FIRSTLIGHT Capital, Inc. Associate

2022.09.20

Here at FIRSTLIGHT Capital, we regularly deliver useful content on both Japanese and global startup trends, as well as hands-on experience from our very own venture capitalists and specialists. Please feel free to contact us via the CONTACT page if you would like to be in touch. Click here to follow FIRSTLIGHT Capital’s SNS account!